The Symbolic Literature of the Renaissance

Support the Library!

Buy your books here.

home

authors

books

contributors

books for sale

links

| ||||

|

|

The Library of Renaissance Symbolism The Symbolic Literature of the Renaissance |

|

||

|

Support the Library! |

Find On Worldcat |

Find On This Site |

||

|

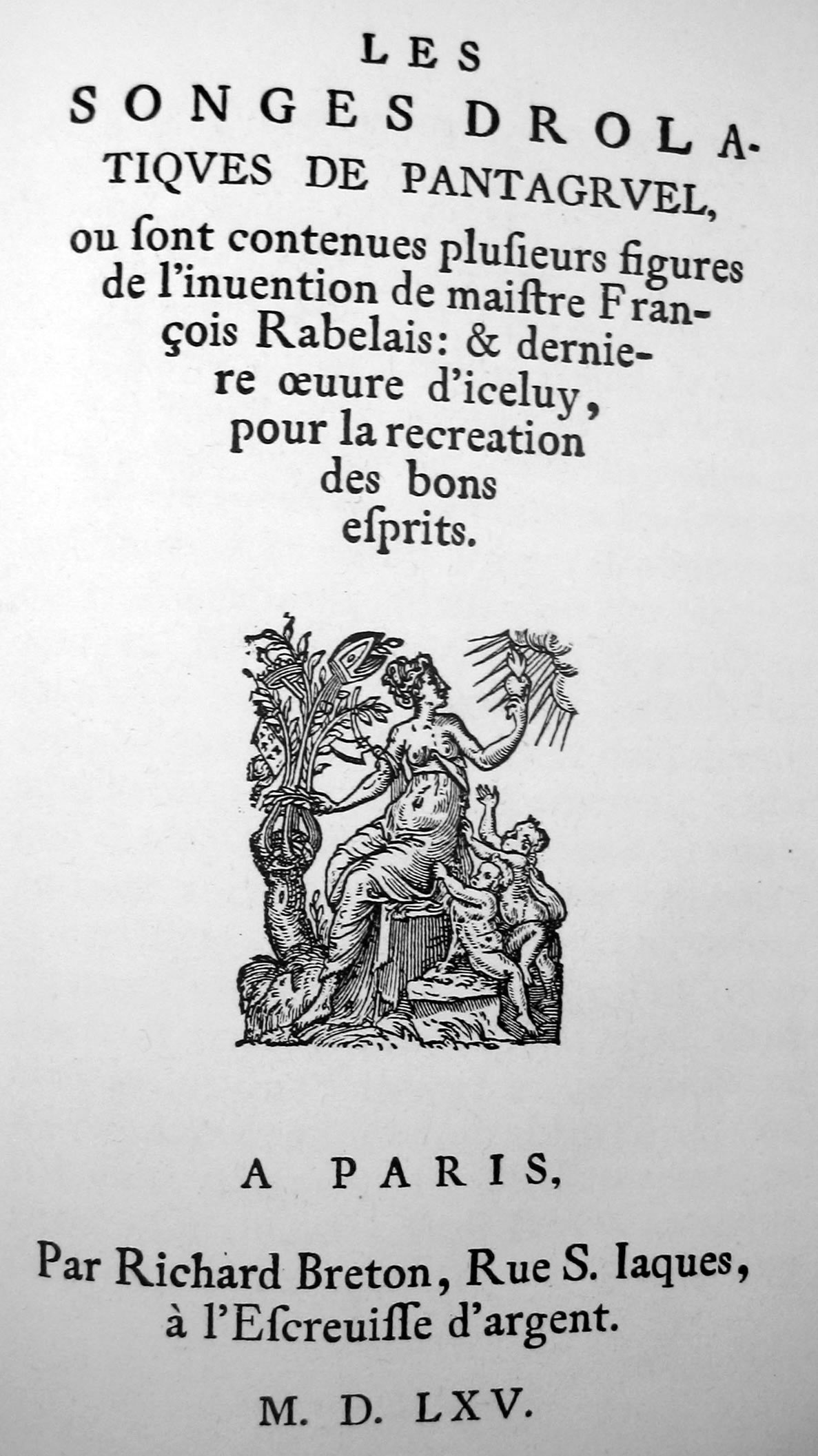

Les Songes Drolatiques de Pantagruel

Rabelais’ masterpiece Gargantua and Pantagruel was published in four books and in many editions from 1532 to 1552. A fifth book was published posthumously in 1564 under the title L’isle sonnante, the Ringing Isle, but the authorship of this last book has been disputed although it certainly exhibits the brilliantly ascerbic and scatological style of the earlier books. The whole work is one of the great satires of all Western literature castigating, without shame or pity, the institutions, culture and society of the time. It became immediately popular but, not unnaturally, also provoked intense opposition, particularly from the Church authorities, and it was later placed on the Index of Forbidden Books. Les Songes Drolatiques de Pantagruel, from which the present images are taken, was first published in 1565 by Richard Breton in Paris. It consisted of an introduction and the 120 cartoons which I am displaying here. The cartoons in the original edition had neither titles nor descriptions but presumably were intended to be illustrations of characters from Rabelais’ work. This original edition gives us little further help or information as to the author or artist indicating only in the brief introduction that the publisher knew Rabelais well and therefore decided to bring ‘this last of his works to light. We can note that the publication of Gargantua and Pantagruel quickly inspired imitations, commentaries and parodies by other writers, one of the earliest of which was a long poem by François Habert published in 1542 based on Rabelais’ first and second books and called, perhaps significantly, Le Songe de Pantagruel. Another such was the Les Navigations de Panurge (Lyons: de Tours, 1543). It need not surprise us therefore that, in the case of the Songes Drolatiques, the enterprising publisher or the anonymous artist may have thought to take advantage of both Rabelais’ material and his name to publish what he hoped would be a best seller although there is at least one suggestion that Rabelais himself could have arranged the book’s publication as a response or as an accompaniment to Habert’s poem. Two of the images include the initials AN or Alcofribas Nasier, an anagram of François Rabelais, and the name which was used by Rabelais as the author of the first two books of Gargantua. It has also been proposed the artist of the Songes was one François Desprez principally because he signed the dedication to another work also published by Breton in the previous year, 1564, the Recueil de la diversité des habits, a Collection of the diversity of dress, illustrated by images not wholly dissimilar in style from the Songes Drolatiques. I show here two of the most similar of these pictures from Desprez’ Receuil. In my own view, they are not nearly of the subtlety or artistry as the images from the Songes. You can form your own judgment. Whatever the immediate inspiration for these pictures, they take their place, and perhaps represent a climax, in the wider context of grotesques, drolleries and monstrosities each of which had a long tradition in the literature of the Middle Ages and Renaissance. The grotesques and drolleries which are depicted in the margins of manuscript illuminations of the Middle Ages (and in the ecclesiastical sculpture of the time), had a revival in the 16th century in the work of Bosch and Van Breughel both of whom were contemporaries of Rabelais (see some examples of drolleries from the early 16th century Book of Droleries or Croy Hours here). Books of monstrosities were also common-place during this time. For example, we can take, just from the French canon, Boiastuau’s Histoires Prodigeuses of 1561, the Prodigeuses of Lycosthenes of 1557 and Ambroses Paré’s Des monstres et prodiges of 1573. The popularity of this genre reflects the growing interest in the reports of Renaissance travellers, and is another illustration of the moment of transition from the medieval age of fable and allegory to our modern age of empiricism and what we call the natural sciences. The present images are taken from the second printing of the Songes Drolatiques which appeared in 1823 as the last volume of an edition of the complete works of Rabelais. For this edition, the images were recut with astonishing accuracy but lack something of the delicacy of those in the first edition. The editors of this second edition added references to Rabelais’ work for each of the images but these references are now regarded as almost uniformly fanciful and worthless. There is a suggestion that the images are to be viewed as pairs, the first as a monstrosity and the second as a drollerie but, personally, I find such distinctions difficult to detect. |