|

|

More SlideShows

|

(click image to go to each slideshow) |

|

|

The Hieroglyphica of Horapollo, probably written in the 5th century AD, and rediscovered in Greece in 1417, was a revelation for the Renaissance humanists since for them it seemed to justify the obsession of the age, the belief that symbol and allegory were the key to an understanding of the ultimate realities. The book consisted of an exegesis of the meaning of a number of Egyptian hieroglyphs although most of the descriptions are now generally regarded as fictitious. The original manuscript, which was first published by Aldus in 1505, had no pictures and the following slide show is taken from the Kerver edition of 1551 which is formatted like an emblem book. The pictures are based on drawings by Durer which illustrated a manuscript of the Horapollo edited by Pirckheimer and now in Vienna. |

|

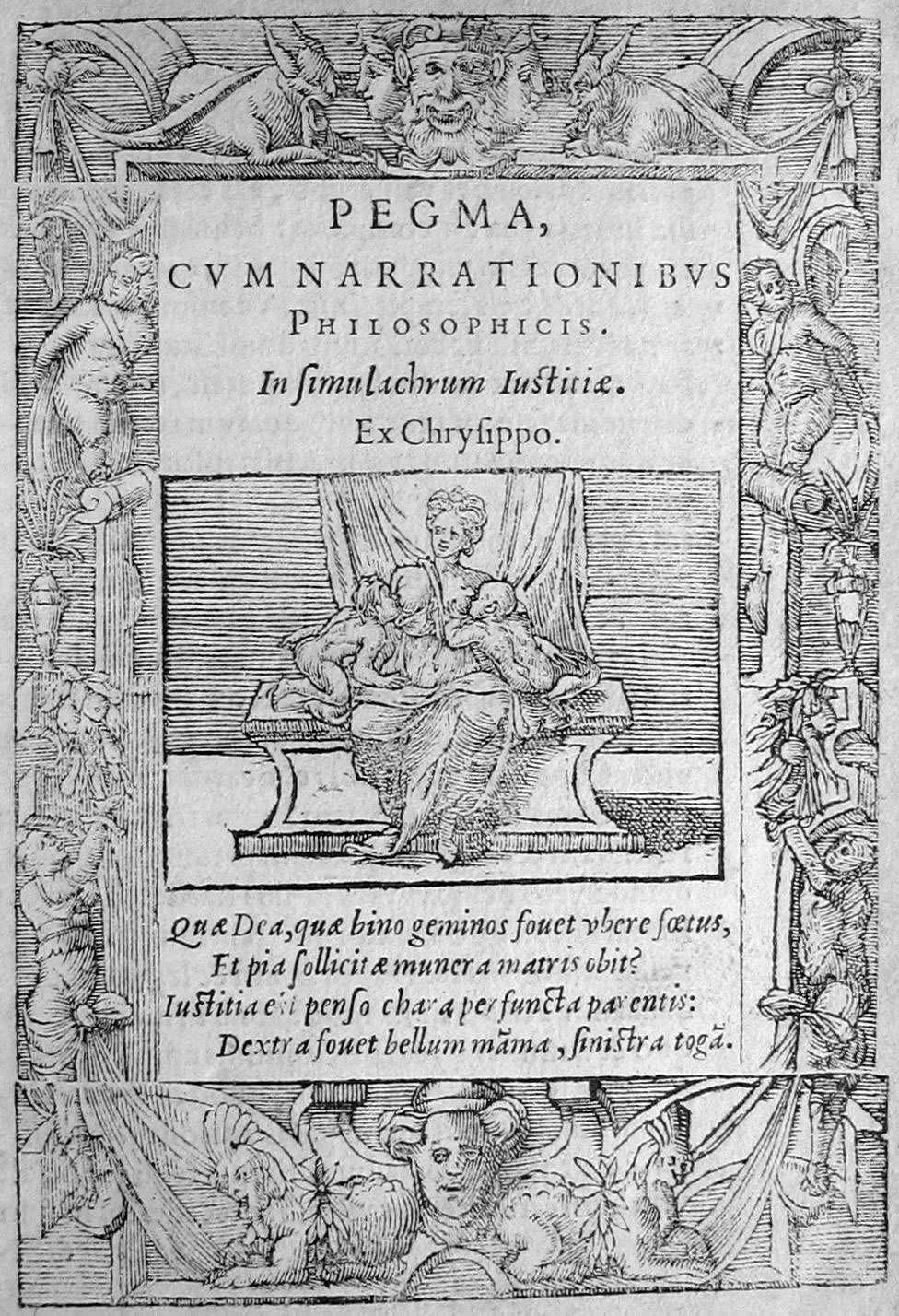

Pegma is a rather rare Latin word which was used in antiquity and the Renaissance to mean some kind of structure: a bookcase, a scaffold or a mechanism in the theater for raising and lowering objects. We get a clue from the index of Coustau’s book which is entitled Index Epigrammaton quae Pegmate continentur or Index of Epigrams which are contained in the (bookcase, structure, theater). Perhaps the best translation is ‘staging’ which resonates with titles of other emblem books of ‘theater’, (e.g. La Perrière’s, Le Theatre des Bons Engins, the Theater of Fine Devices, of 1539) and reflects the elaborate stage mechanisms of contemporary pageants and festivals. The idea of stage machinery as symbol possibly originates from Plato’s use in the Republic (518c) of the word periactoi in his description of the soul turning from the darkness of the Sensible world to the light of the absolute and eternal Forms or Ideas. In Greek theater, the periactoi were small canvases with scenery painted on them and fixed on spindles which could be turned to change the scene. |

|

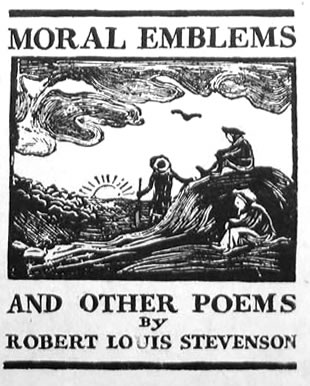

These are the emblem images from the first American edition of the last original emblem book of the 19th century by Robert Louis Stevenson, the novelist. It was originally published by Lloyd Osborne, his 12 year old stepson, who concerned about the desperate state of the family’s finances when they were living in Switzerland in 1882, used a toy printing press to publish leaflets and menus and eventually, this book, the Moral Emblems. Stevenson wrote the poems for the book and also carved the accompanying woodcuts. The emblems reflect Stevenson’s lifelong and bitter cynicism of middle class material values. |

|

John Bunyan of Pilgrim's Progress fame also wrote an short emblem book which was first published in 1686 with title of ‘A book for Boys and Girls or Country Rhymes for Children’. It went through a number of editions and eventually the name was changed to the present title. The following images are taken from the 1806 edition. The emblems give quite simplistic, moral admonitions suitable for children. |

|

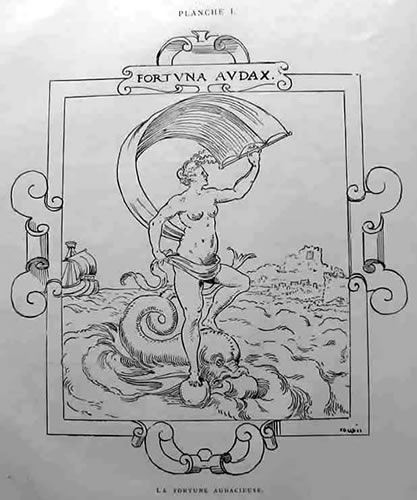

The Goddess Fortuna was almost the only Roman deity who survived into the Christian era and in whom there was continuing interest from Roman times right up to and through the European Renaissance. Many authors of note from the period wrote treatises on the subject and on the associated topics of Casus (Chance), Occasio (Opportunity) and Nemesis (Retribution) and the emblematists continually also used the topic in one form or another. These pictures come from a 19th century facsimile of a 16th century manuscript emblem book, the Liber Fortunae, with 100 emblems all of different aspects of Fortuna. The drawings are by Jean Cousin, perhaps the most famous French illustrator of the 16th century. |

|

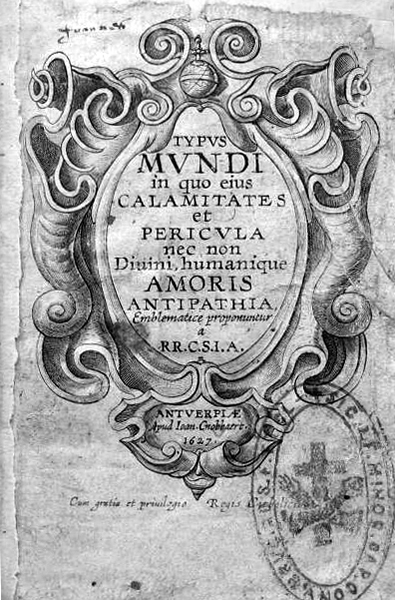

Typus Mundi This book looks like a typical devotional emblem book but was written actually as a class project by students at the Jesuit college in Antwerp. There are thirty-two emblems and the names of the students responsible for each one are given at the back of the book. Apart from the picture and the Latin poem there is one epigram in French and one in Dutch for each emblem, all contributing to an understanding of the whole.

The theme of the book, given in the subtitle, is the calamity and danger of a world in which the love of God and the love of man are opposed. Despite its simple origin, the book became quite popular and went through 4 editions. Some commentators profess to find an underlying alchemical progression through the book. Together with the Pia Desideria it formed the basis of Emblems Divine and Moral, the highly successful English emblem book by Francis Quarles. |

|